Project 'P6BS'

Tests and Reports

1967 - 1968

The experiment that escaped - Motor - issue 30 March 1968

The Rover/Avis BS - unfortunately not for sale

by Charles Bulmer BSc AFRAeS

Drawing: by Brian Hetton MSIA

Although this car is an engineering exercise and the styling is incidental, it has a certain something that gives it a distinctive character of its own. It would be perfectly acceptable as a production model. All manufacturers make experimental cars to try out their ideas. Some of them are dreadful and best forgotten, some are instructive, some of them are so good that they eventually go into production. Others should go into production but the finance, the manufacturing facilities and the engineering talent of the company are already too tightly stretched to add another model to the programme. This is the story of a car which belongs to the last category but whereas most of these research prototypes live and die in total secrecy, this one will not. lronioal to think that one of the most interesting cars that never made the showrooms was the Issigonis-designed Alvis V-8 of some 12 years ago - and this one too might have appeared as an Alvis V-8.

The idea was born in the Rover factory a few years ago when the success of the Rover-BRM and the availability of a number of very suitable components (Rover 2000) was causing the management to think about sports and GT cars and the design staff to exchange sketches on the backs of envelopes. Some of these were front-engined, but a good look at what was happening in the competition world suggested that the days of the front-engined sports/GT car were, if not over, at least numbered. There was one other important factor at this time - William Martin-Hurst, Rover's energetic Manaing Director, was laying the foundations for developing the Rover V-8 3½-litre light alloy engine from the Buick version which the Americans were abandoning in favour of cheaper cast-iron production. Weighing, as it does, only the same as the 2000 unit, this was the obvious choice for a car intended to have real performance. Since most people don't associate Rover with a sporting background it might be appropriate here to mention that this is not true of those most concerned in this story. Peter Wilks (now Technical Director) and Spencer King (Chief Engineer, new vehicles), together with George Mackie, used to race Mackie's old Talbot in the late ‘forties. About 1949/1950 they built the 2-litre Rover Special single seater, a Formula 2 car which had an early version of the current de Dion rear suspension (with fixed length half shafts), and later on the Marauder. Span King, who was then working in the Gas Turbine department, was also responsible for the Earls Court T3 turbine coupe as well as the Rover 2000; some of those who know him well regard him as the most brilliant of the younger designers in the industry today.

Beginnings

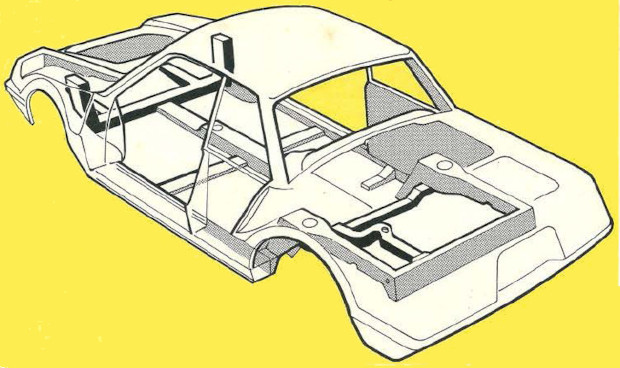

This was, of course, a low priority project. Gathering together all the bits and pieces which would or might be useful, Spen King and his right hand man, Gordon Bashford, dumped them on the floor of the pattern shop - the only quiet and peaceful spot they could find. It was here that the ingenious transmission layout was decided in principle and this, of course, is the key to the whole design. The disposition of other major components was also settled in broad outline and it was found that a welded one-piece steel body structure would be the most convenient to use, and the cheapest. This, however, led to an impasse since the next step was to fix the exact position of engine, suspension, passengers, equipment, etc. and draw the structure around them and this was only possible when a body shape had been fixed. The Rover styling department was working flat-out on higher priority projects at the time and couldn't spare the effort. In the end the engineering department did the entire body design and styling themselves with some helpful advice from one of the stylists which alone makes the car a rarity. If they were doing it again they would make certain modifications - to conceal the exhaust silencer for example - but the result is interesting and different. It is exceptionally functional and compact in the same sense as a Mini - it encloses a maximum of useful space inside, minimum external dimensions and many people like its purposeful, rather aggresive appearance. It is unusual, incidentally, in having a windscreen of constant radius to avoid the optical irregularities which arise from changing curvature. The drag coefficient is only moderately good (about 0.42) and had it gone into production it might have looked entirely different - but it might not.

From the structural point of view perhaps the most interesting thing about the general layout is that major loads are fed in at almost ideal positions. As shown in both the main and body drawings, roof pillars, rear bulkhead and rear suspension mountings all converge towards one nodal point at the back and a similar condition obtains at the front where the passenger foot box extends forward to the wheel hub axis (this is fundamental to the design of a compact rear-engined car) - and the front suspension is bolted directly to the front bulkhead. All this helps towards the achievement of an overall weight of 21 cwt. — low for a steel-bodied 3½-litre car with wheels, brakes, tyres and running gear designed for 140 m.p.h. stresses. The detailed design and drawing of the running gear and transmission was undertaken by Alvis engineers under the able guidance of Mike Dunn — now Chief Engineer (Forward Projects) at Leyland - it then seemed possible that the BS (its code number) might be marketed as an Alvis.

| Images from the article | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||

|

Above: Left: |

Above: Right: |

|

| The illustrations in larger format are located in the section ⇒ Technology | |||

Suspension

Front suspension design almost settled itself to suit the spatial layout. It has double wishbones with an unusually long king post in order to get the top wishbone to a height where its length is not restricted by foot room and to the same level as the rack-and-pinion which is above the passenger's feet. The steering rack (from a Viva) is mounted upside down, so that it steers the right way, and has turned out to be much too low geared. The suspension was originally built without anti-dive geometry and with zero camber and caster but the latter had to be altered later. Rear suspension was based on that of the Rover 2000 with lateral location by fixed equal length half shafts, longitudinal wheel location by radius arms forming Watt linkages in side elevation and a telescopic de Dion tube to control steering and camber. lt differs, however, in that the disc brakes (Lockheed in this case) have to be mounted outboard instead of inboard since one side of the differential is tucked into the engine sump. The coil spring/damper units all round are designed for about the same static deflections as the 2000 saloon (8 to 9 in.) so this is a really softly sprung GT car.

Engine and transmission

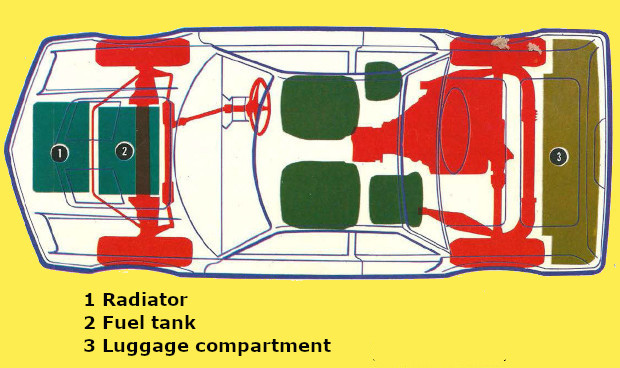

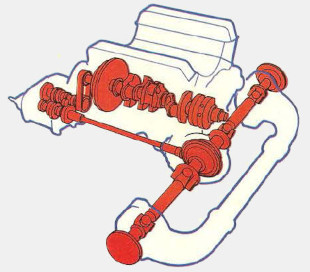

The engine and transmission form the most ingenious part of the design, as shown in the accompanying diagram. The clutch/flywheel unit of the V-8 engine is at the forward end of the car and drives an offset gearbox through a Morse Hy-Vo chain at a 1 : 1 ratio. The drive then goes aft through an open shaft alongside the engine to a Rover final drive unit recessed into the sump and fitted with a four star differential and 4.1 : 1 final drive ratio. It follows, therefore, that the engine is offset to starboard but the amount of offset is surprisingly small - about 5 in. The gearbox is basically a Rover 2000 unit, lying on its side and fitted with an aluminium-bronze mainshaft bush, an oil pump, and gears with their tooth roots shot-peened for strength. The drive does not enter through the primary shaft in the normal way but, instead, the chain sprocket drives the layshaft direct with various desirable consequences. The torque which the box has to handle is reduced - normally the layshaft torque is equal to engine output torque multiplied by the reduction ratio of the constant mesh gears but here this multiplication does not exist. The constant mesh gears only come into operation in top when the drive goes back through them to the primary shaft and thence straight to the output shaft in the normal way. Top gear torque is therefore similarly reduced and top is, in fact, an indirect gear giving a step-up ratio which allows exceptionally effortless cruising at about 27 m.p.h. per 1000, r.p.m. Finally, it will be noticed from the main drawing that the connection from gearlever to gearbox is remarkably short, simple and direct - not often a characteristic of such designs.

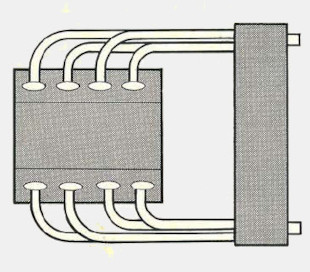

When construction started the Rover V-8 engine did not exist and the car grew round its ancestor, a second-hand Buick V-8 which had been modified for racing with solid tappets and multiple carburattors. It didn't work very well for reasons which gradually became plain - one camshaft lobe, for example, had worn right off - and when the time came to look at the engine seriously it was rebuilt to standard Rover specification with hydraulic tappets but with 2 in. (TC) SU carburettors instead of 1½ in. In this form it gave 175 b.h.p. on the dynamometer, using the shop exhaust, but output dropped to below 150 when the car's exhaust system was put on. Now this engine has a two plane crankshaft and readers who are familiar with V-8 design will realise what complexity is involved in building an exhaust system to avoid blow-back interference — to get even 360° pulse spacing it is necessary to interconnect cylinders in opposite banks of the V. However, Spen King discovered that it was possible to devise quite a simple (though unsymmetrical) arrangement which would ensure that no inter-connected cylinder will interfere with another - in fact, each such pair (see accompanying diagram) fires at 270° and 450° intervals and the effective valve opening period is less than 270°. With the silencing arrangement shown in the main drawing, this modification alone raised the power output to 185 b.h.p. at 5,000 r.p.m. - an increase of over 35 h.p. compared to the original system — without making the car noisy: rather smallbore pipes are found to give the best results. This is virtually installed power - tested with all normal accessories except the generator. Strangely enough no record has yet been discovered of such a system having been used before and the Rover engineers are anxious to try its equivalent on the intake side as well, using four carburettors.

There is, of course, no engine-driven fan since the radiator is front-mounted; air goes in through the low grille and out through the slots in the top of the bonnet and a thermostatically controlled electric fan boosts the flow in traffic conditions. Air for the heater is taken in around the headlights and thence through the double skinned wing sections to the plenum chamber, and engine room air is admitted through slots ahead of the rear wheel arches.

Development

The BS has now been running for about a year but only for very occasional tests on secluded circuits. Security has hitherto kept it off the public roads although, by the time this appears in print, it should have had a substantial outing in Scotland for our road test, elsewhere in this issue. Early development tests showed that it didn‘t have many serious faults although the damper settings had to be made much stiffer and the castor angle raised to 3° plus some mechanical trail to cure a directional uncertainty. The worst problem was a very marked throttle-on/throttle-off handling change — so marked that it would corner extremely fast in an understeering condition on full throttle but was liable to spin off if you lifted your foot. No fault could be found with the suspension geometry, and various other expedients were tried. It was found that the spinning tendency could be cured by using an excessively strong front anti-roll bar — so strong that the inner front wheel would lift — but this made the ride feel unpleasant and the car lost cornering ability. lt behaved extremely well on racing tyres but not on ordinary radials. ln the end a solution was found by using 185-14 Cinturatos on 5½ in. rims at the front and 185-15 Cinturatos on 7½ in. rims at the back. Since the latter have a very low profile there is little difference in overall diameter between front and rear but there is a substantial difference in cornering power. It is now, perhaps, over-stabilised from a competition point of view but Rover believe, quite rightly, that a road car must be developed so that a very ordinary driver can do all the wrong things and still not lose it. Since this throttle sensitivity is common in greater or lesser degree in many cars, it may be worth looking very briefly at possible reasons why it is more powerfully present in this one. Basically the answer seems to be a high torque/weight ratio and tyres which are more than generous in size and capacity relative to their load. At full throttle in the 80 m.p.h. second gear there is a driving torque at the back wheels probably in excess of 1,200 lb.ft. which tends to lift the front of the car; so going from full to no throttle in second will produce a weight transfer of about 150 |b., i.e. 150 lb. load will be removed from the rear tyres and added to the front ones. Suppose, however, we err on the cautious side and call it 100 lb. (i.e. 50 lb. per tyre) so that on lifting off each rear tyre load drops from, say, 650 to 600 lb. and each front one rises from 550 to 600 lb. The accompanying graph (not actually for the tyres in use but adequate for illustration purposes) shows that the effect at 10° slip angle is to lose about 25 lb. from the rear cornering force and add 25 lb. to the front or, putting it another way, there is a total change of about 2° slip angle towards oversteer. Had the same tyres been fitted on a car with less torque and greater weight so that the tyres were running near their rated load of about 1,200 Ib., the change would have been negligible since the tyre operating point would have been near the horizontal section of the curves — which is the common condition for most ordinary cars.

A full specification, detailed dimensions and performance figures will be found in the road test of the car. But to whet the appetite for what might have been, here are two parting thoughts. The BS was costed for production and it could have been sold for the same price as a Rover TC — say £1,500. And finally the V-8 engine, unlike most current sports car engines, is only at the beginning of its development — tucked away at Solihull are two Traco-modified versions, one giving 320 b.h.p. and the other 270 b.h.p. and 270 lb.ft. torque.

© Motor

© 2021-2026 by ROVER - Passion / Michael-Peter Börsig

Deutsch

Deutsch