Project 'P6BS'

Tests and Reports

1967 - 1968

One-off Dream - Motor - issue 30 March 1968

One-off dream

Three-seater experimental Grand Tourer with 3½ litre V-8 engine amidships; superb traction and roadholding; 140 m.p.h. and tremendous acceleration; comfortable and refined

For the past eight years, mid-engined cars have utterly dominated the international racing scene yet the influence of this reigning breed on production sports and GT design has been virtually nil. The handful of extravagant exotics like Ferrari, Lamborghini and Ford‘s GT 40 are separated from the clutch of much cheaper, but largely impractical, mid-engined fun cars like the Lotus Europa and Unipower GT by only one really same member of the family, Matra’s M530. And even on this, the major inherent advantage of the layout - a rearward weight bias for good traction - is barely exploited by the engine’s modest power. (Anyone who has driven, say, an American sporting compact will know all about the embarrassing limitations of wet-road adhesion in a powerful front-engined rear-drive car). But traction isn’t the only advantage of a mid-engined road car: with the engine tucked away behind, the bonnet can be short and raked to give a commanding view out, while lightly laden front wheels permit featherweight, yet high geared, steering without recourse to power assistance. The only real stumbling block, so we had been led to believe by most existing designs, was how to fit people and luggage round an engine and gearbox that occupied so much valuable space in the structure.

Enter, here, the Leyland Rover BS experimental car which not only convincingly endorses the predictable virtues of a mid-engined layout but also demonstrates that ingenuity can overcome the problem of accommodation, even in a compact car with a wheelbase only three inches longer than that of an MGB.

A full description of this unique and fascinating machine appears on pages 33 to 38 of this issue so we will not explain here how and why it came into existence. Briefly, it was designed as a really modern, compact grand tourer that could match the best sporting machinery in traction, roadholding and performance, and a civilized saloon in comfort and refinement - at a selling price of around £1,500 it is a very low, striking three seater - which is no more impractical than a 2+2 - with a slightly tuned 185 b.h.p. version of Rover’s light-alloy 3½-litre V-8, nestling - suitably shrouded to keep the noise level impressively low - behind your neck (or by your side if you are in the back as the engine is offset to the right): it drives the massive back wheels through a four-speed manual gearbox. Whether you use all the gears or not, (and the notchy change did not inspire frequent ratio changes) the performance is terrific and the traction, despite the car’s modest weight of little more than a ton, probably superior to that of any other road car around.

As a secret prototype, it had never been driven in earnest on public roads before our testing session in the Scottish Highlands so we discovered, perhaps before even Rover found out for themselves, how supremely agile and inspiring it is to drive fast, despite a few detail faults like excessively low-geared steering, spongy brakes and an unprogressive throttle action - all of which would very quickly be eradicated by further development.

To us, perhaps the most impressive thing about the car is that it could almost have passtxl for a fully-sorted, finished product: it is hard to believe that, as a low-priority project, it has in fact undergone little more than spare time development since being built (at the Alvis Factory) straight from Spen King’s design office using as many existing Rover components as possible.

Safe, usable performance was only part of the brief, though, because the BS, even in this one-off prototype form, is quite a refined and comfortable car. Like the Rover 2000 (from which the de Dion rear suspension comes) it rides superbly without pitch or roll, and little or no further work would be necessary to reduce the already faint wind and road noise. While there are inevitable deficiencies and faults in the car‘s equipment, it is significant that, were we to treat this as a normal road test report, our criticisms would be aimed only at details, not fundamentals. To have got a car so very nearly right without any serious development suggests not only competent design work but also that the finished product really could be a world beater.

Performance and economy

The description on page 33 explains how changes to the carburation and exhaust of the otherwise standard lightweight V-8 boosted power to 185 b.h.p. - 25 more than the big 3.5-litre coupe has in a car weighing half a ton less. The resultant healthy power/weight ratio of I75 b.h.p. per ton spells capital P Performance. Even in this still relatively mild state of tune the BS will match a 4.2 E-type to 100 m.p.h. and actually beat it to 60 m.p.h. Consider that the engine is capable of giving well over 300 b.h.p. and that the prototype‘s drag coefficient could no doubt be improved and you begin to realise the car’s enormous untapped potential, not just for high-speed road work but perhaps for competition too. Clearly, the car’s maximum speed was much too fast for MlRA’s banked track; as we didn’t take it abroad, either, the exact top speed remains unknown both to us and to Rover, who have never fully extended the car. Assuming it could reach peak power revs (5,200 r.p.m.) in top, though, the maximum would be somewhere around the l40 m.p.h. mark in its present form; but with 300 b.h.p. in a more aerodynamic shell . . . .

Restricted breathing on the standard V-8 limits its effective r.p.m. to little more than 5,000 before the power tails off. The modified BS version, which inhales through bigger carburetters and discharges through a free-flow exhaust, has a hearty, responsive pull from 600 to 6,000 r.p.m. (mechanically, the engine is safe to even higher speeds - though not with the standard hydraulic tappets as oil frothing can occur and destroy the lifting cushions). Despite exceptionally high gearing the engine will pull from under 20 m.p.h. in top in a brisk, clean surge. the rise in torque as the revs increase just about matching the build up in drag, witness the 80-100 m.p.h. time of 9.1 seconds - barely a second longer than that needed from 20 to 40 m.p.h. Third gear performance is even more impressive as it will thump the car vigorously from 10 to 100 m.p.h. (no 20 m.p.h. increase takes more than 4 to 6 seconds) and is therefore a splendid B-road ratio that will drag you smartly out of sharp corners and waffle along smoothly at 70 m.p.h. between them.

There were, however, two distinct and separate vibration periods on the prototype which marred its otherwise silken pull. One - a hard ra-ta-tat - was evident under vicious acceleration in first or second, and possibly caused by engine torque twisting the exhaust, or some other component, into physical contact with the chassis; the other, which Rover thought could be eliminated by changing the engine mounts, was a much milder shake at about 2,500 r.p.m. Apart from this, the V-8 was magnificent: it “blipped“ like a racing engine and even the exhaust note - well muffled but sufficicntly strident at high revs to be exciting - seemed just right for a refined sports car, though the intake hiss from the carburetters (displayed above the engine deck in a transparent plastic eye which stares at you through the mirror) could well be reduced. As there were no silencing air filters in the big 2-inch SUs it is surprising, really, that there isn’t even more intake roar.

As in performance, so in economy, the BS is uncannily like the E-type: for both, the top gear consumption curve extends from around 30 m.p.g. at 30 m.p.h. to 20 m.p.g. at l00 m.p.h., the Jaguar's bigger engine perhaps being offset by better streamlining. All our spirited test driving was done on deserted roads in Argyllshire - the sort of streak-and-brake driving which, from past experience, we have found to be the heaviest on fuel. So it is quite likely that under more typical conditions, our overall consumption would have been well into the twenties. And for a three-seater 140 m.p.h. car, you can’t grumble at that.

| Illustrations to the article | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

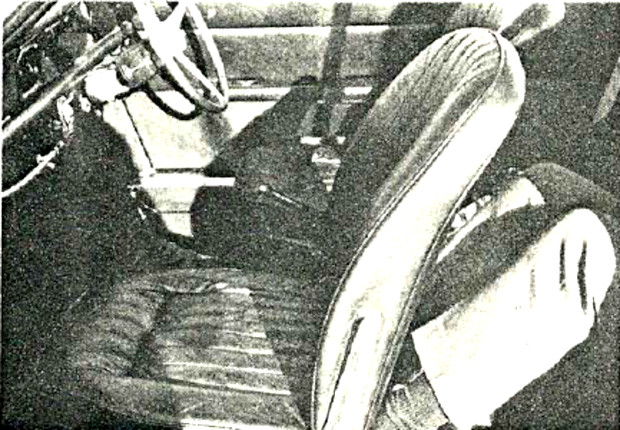

| If the passenger seat is moved further forward the "third man" behind it can sit relatively comfortably. |

Under the front bonnet are the fuel tank and spare wheel. | The boot behind the engine is narrow but wide. |

| The detailed specifications and dimensions can be found at ⇒ Specifications | ||

Transmission

Reference to the description and drawing will reveal details of the ingenious transmission design. From the driver’s viewpoint, though, it seems entirely conventional except for a slight whine in top which betrays that all the gears are indirect. In fact third gear, unusually, is quieter than top, another point in its favour for secondary road driving. The strengthened, offset 2000 manual gearbox, driven by a chain from the clutch on the forward end of the engine, has a splendid set of ratios - closely spaced and all high so that second, even first, can be used to catapult the car past quite fast moving traffic. At 27 m.p.h./1,000 r.p.m. top gear is exceptionally high so the engine is spinning gently and quietly at a mere 3,700 r.p.m. at 100 m.p.h.

The gearchange itself, though, was disappointing because synchromesh obstruction, accentuated by the short lever and the indirect layshaft drive which makes the cones operate on components running at higher speeds, seemed excessive on the BS and barred quick flick-switch down changes into second when approaching a slow corner. A longer and closer gearlever would have made the gears much easier to locate. The clutch did not seem nearly so heavy as the 40 lb. indicated by our meter, probably because you attack the pedal from the right height and angle. It has a fairly short travel yet not a sudden or unprogressive engagement.

Handling and brakes

Our first session with the car one cold, bleak Sunday at the MIRA test track was, from a handling point of view, disappointing. It seemed to suffer from excessive understeer under power and a sudden reversal to neutral, or oversteer, when you lifted the throttle - an action which called for rapid untwirling of the rather low geared steering if the car was not to leave the road on the inside of the corner. Hindsight makes it clear that a lot of this untidy behaviour stemmed from driving, for the first time, round an anticlockwise circuit on tyres that had been well and truly worn off on a clockwise one. Certainly, with new tyres and less flexibly mounted steering gear, the car’s handling and roadholding felt vastly improvcd - and by any standards very impressive - for road work. Half way through our test in Scotland we had the second (of two) front anti-roll bars removed (it had been added as an experiment after someone had spun the car during a Mallory Park session): this rcduced the understeer to a level that we thought just about right without making the car at all unstable. With massive 7½-inch wide back tyres (against 5½-inch front ones) it was virtually impossible to power slide the car, so, on a dry road at least, full throttle could be used in second out of quite sharp corners without getting out of line. In fact we cannot recall driving any other road car with more sheer glued-on adhesion than this one on its special Pirelli Cinturatos.

The only further modification obviously needed - which Rover agree should and would be made - is to fit a quicker steering ratio. The l¼ turns needed on a 50-ft. circle put it on a par with, say, a Ford Corsair or Vauxhall Cresta: 0.8 or 0.9 would be nearer the sports car mark to make the steering more responsive. At present, the steering is so light that an increase in weight of up to 50% imparted by higher gearing would be quite acceptable, the residual understeer from just one anti-roll bar being sufficient to ensure that quicker steering did not make the car feel twitchy. A little kick-back through the rack-and-pinion made even the present low-geared linkage feel nicely alive and informative, though on a rough surface it could kick quite strongly.

The throttle steering evident on MIRA’s road circuit had been almost completely eliminated by the tyre change for our testing in Scotland where the car felt uncannily stable and reassuring to drive fast over unfamiliar roads. This confidence stemmed not only drom the splendid feel and balance of the car, its tremendous road-holding and cornering powers and almost total absence of inhibiting roll and lurch, but also from the driver's commanding view over the short bonnet through a massive windscreen (a slightly distorted “one-off”) supported by very slender pillars. The view aft when reversing was equally good.

Our first impressions of the brakes at MIRA was that they worked very well at low speeds (our Tapley recorded well over 1g) but that a panic stop from above 80 m.p.h. needed a hard, spongy push on the pedal. A change of pads and freeing of seized cylinders before going to Scotland certainly removed any doubts about their stopping power - which was very impressive - though the rather woolly servo response still induced a soggy pedal action and there was too much threshold free play. A minor gripe we had about the height of the pedal above the accelerator - which made heel-and-toeing awkward - was answered by Rover with a few minutes’ spanner work. Perhaps it is a reflection of the soundness of the car’s basic design that little details like this were the most conspicious faults. The handbrake - which on a rear-engined car with plenty of weight on the back wheels should be good - seemed to have very little bite; but presumably this is a curable defect.

Comfort and controls

To achieve optimum standards in roadholding and riding comfort may still demand theoretically incompatible suspension designs but the BS proved that the practical compromise can be so good as virtually to disprove the rule. Certainly, this Rover would gallop over indifferent roads with impressively little body movement and its behaviour on, say, sharp hump backs (which seem to abound in the Western Highlands) was exemplary: instead of a crashing thud down to earth after a sudden vertical lift, the body is lowered gently on its extended springs. Apart from a slight side-to-side oscillation over certain surfaces, the ride is conspicuous for the almost total absence of pitch, roll and rock on normal roads. The comfortable, resilient bucket seats (borrowed from an E-type) provide good lateral support though we tended (as in the 2000) to slide forward on the rather flat-mounted cushions. Without any forward engine or transmission bulges, the footwells extend right forward to give really generous leg-stretching room though the front wheel arches intrude quite prominently and force the pedals towards the centre of the car. Not that the offset is ncomfortable, or even noticeable after a time. The smallish wood-rimmed steering wheel is mounted on Rovcr’s familiar tilting column which, allied with really generous seat adjustment, ensured a splendid extended arm driving position, of which the only penalty was that it left the gearlever too far forward.

Although the seats are very low, you don‘t feel at all buried or hemmed in as the windows are very big and the sills and scuttle low. Since there is no trouble in getting in or out, and there is room for three adults, the overall size and layout of the car seemed to us ideal, especially as relatively minor styling alterations could perhaps have made even better use of the available space. To have made the car any bigger would probably have marred one of its greatest intrinsic charms - that of wieldy compact size.

We say “room for three adults” on the assumption that a seat would occupy the nearside space by the engine cowling. As our pictures show, there is sufficient leg and head room here for a third passenger (or a useful amount of luggage) who could lounge in far greater comfort than on the cramped back bench of a 2 + 2. The car’s heating system was at the makeshift stage (in fact it had been hurriedly installed, complete with a knurled brass knob on the facia to switch it on, just before our test) but surprisingly effective, and the ventilation non-existent since there were neither air outlets nor quarter lights. But Rover know all about venting and heating, witness the outstanding system in the 2000, so this would presumably have come with further development - along with a pair of sun visors, thc absence of which was made painfully conspicuous by dazzling sunshine in Scotland.

Fittings and fumiture

To dwell on this aspect of the car’s design would be a bit pointless since further development would probably change the layout in detail, if not in concept. It is by no means a makeshift lash-up, though, the surprisingly good finish, electric windows, carpeted floor, built-in door pockets and magnificent instrument layout indicate how the designers were thinking. The clear, colourful and superbly illuminated instrument dials, housed behind plastic windows, are the result of a previous - and we hope not wasted - exercise by the styling department. Rover 2000 stalks operate the flashers, horn, dip and indicators. The front bonnet locker is entirely filled by the spare wheel and fuel tank but there is a useful hold - deep if rather narrow - behind the engine.

© Motor

© 2021-2026 by ROVER - Passion / Michael-Peter Börsig

Deutsch

Deutsch